I tried flash fiction

It is like a contest with heats, so you get writing prompts and then have 48 hours to submit something. You try to keep advancing (kinda like sports? I think?). The category is flash fiction, which to them means 1000 words or less.

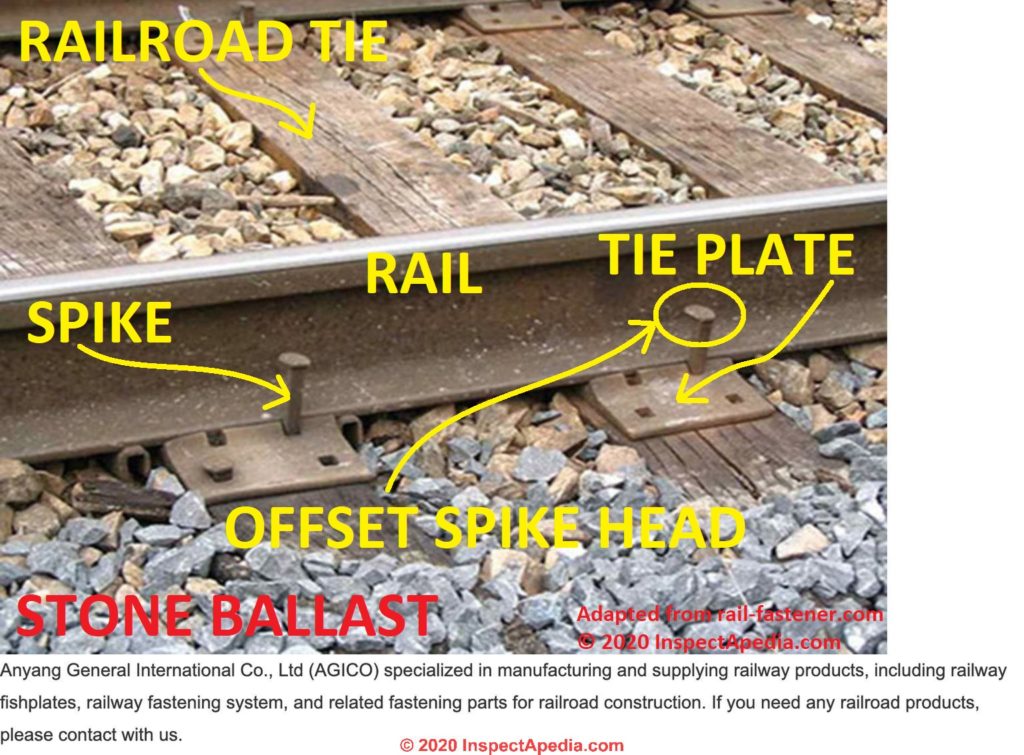

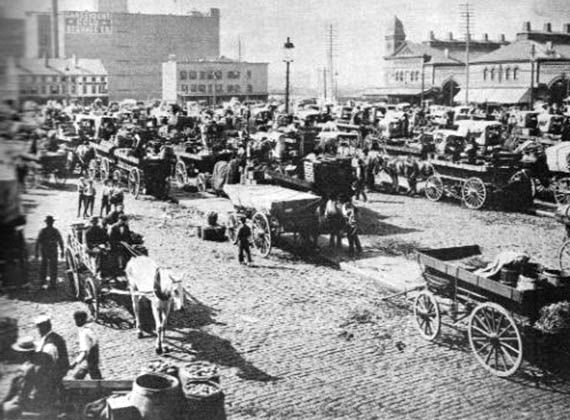

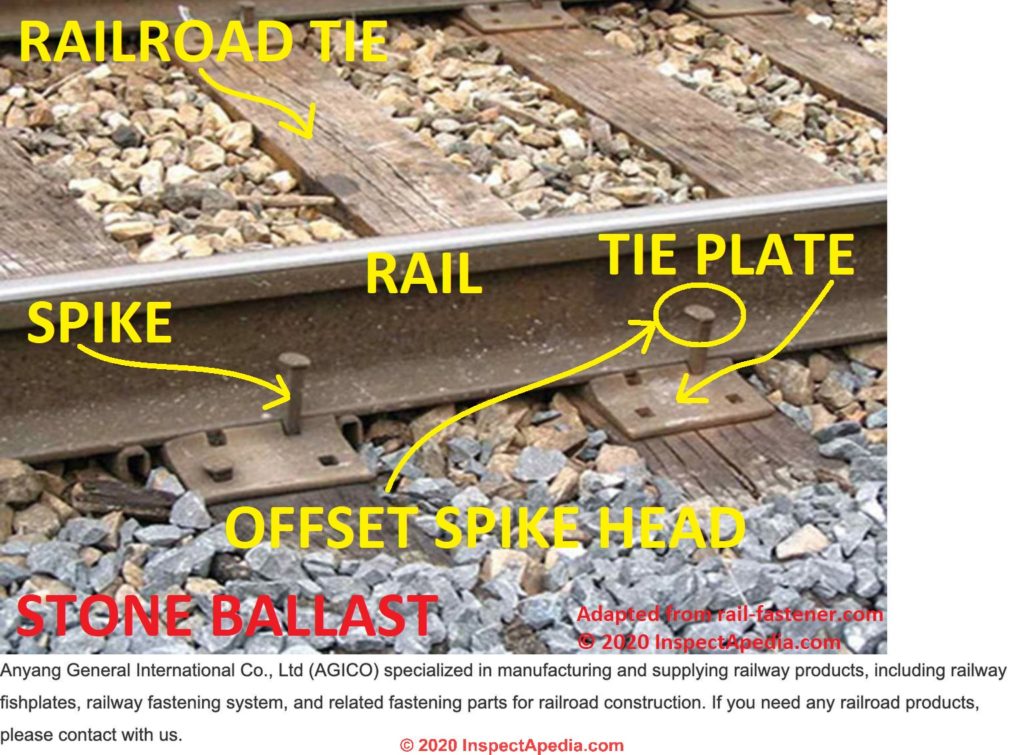

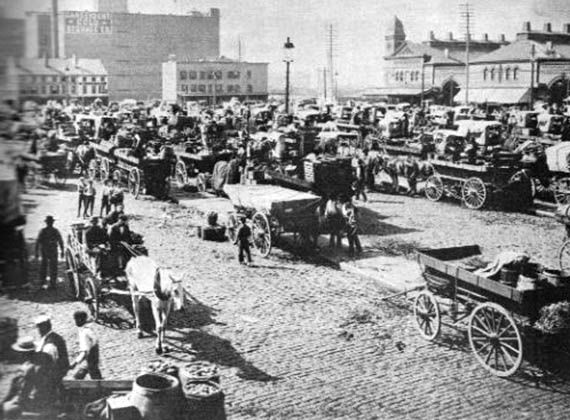

My prompts were: historical fiction, a steak restaurant, and a railroad spike. So I learned about the history of the American railroad, spikes, and steakhouses. I learned about The Old Homestead, the famous steakhouse whose history I try to imagine. Why? Why not.

I looked up some German words and what the meat market in NYC was like, as well as tenements.

I became a German son, businessman, turn-of-the-century butcher.

Tidewaters

In 1868, a German family opened The Tidewater Trading Post in the meatpacking district of Manhattan, establishing the oldest, continuously operating steakhouse in the United States. Much is made about the dishwasher who bought the restaurant in the 1940s, renamed it The Old Homestead, and passed it on through his family to today, yet nothing seems to be documented about the original German owners.

Vati got work as a spike mauler for the railroad in 1833. We moved to the city soon after. He perfected his swing and over time was known to crash an iron rail spike through a tie plate with just 10 powerful strokes. Then move on to the next, and the next, doing the same again and again. Mama said he was the fastest anyone could name, laying 400 meters by late afternoon. The other laborers would find him leaning on his Maul, waiting for them to catch up at the end of the workday.

Vati would be gone from us weeks, even months at a time. When he was home, in our cramped apartment on Gansevoort Street in the low flooded tidewater neighborhood, Mama would rub his shoulders with cooked lard oil stewed with peppers from the neighbors and mint from the garden. The scent filled the tenement and cleaned my sinuses of the thick, river air. On the days he left, Mama hid her tears and gave me heavy chores. With seeming inevitability, the spaces between his returns grew longer. His wage checks came regularly for a long time, but he followed the work west to Ohio and Illinois, connecting town after town and hundreds of farms.

I knew I would never follow him down the rail. Yet, in his way, intentional or not, he paved another path for me. The railroad brought cold meat to our doorstep. As soon as I was old enough, I got a job. I left the tenement before dawn, much earlier than needed, and walked to one of the butcher stalls lining the street, before the hustle and clamor had begun. I laid out my knives and prepared. All morning, men shouted and pushed, vying for the best cuts. After work, I would buy what I could, a leftover scrap. Mama would cook it up with potatoes and we would eat dinner. For years, we went on like this and the rhythm of the days soothed me.

Eventually, Mama wanted me married. I said, “Mama, you get married.” The checks had stopped coming from Vati some time ago. She stiffened and put a finger to my face as though to say, “tell that to your father.” I sighed. She wanted kind, offspring. I could hardly not notice the way she lifted the neighbor’s squalling infants from their buggies, wrapping them in her apron as the mothers struggled up the front steps. She coddled and smelled the babies.

“There, now,” she would admonish with mock scolding. “It can’t be that bad; there, there now. Dort jetzt.”

I began to come home, weary from work, to find company at the kitchen table. “Here he is!” Mama would announce before I shut the door. A young woman with her mother would set down our best cups in their saucers and stand to be introduced.

“What did you find for our dinner?” Mama would beam with pride. “You see, he brings the best!” And she would cook us a hardy meal with fresh baked bread.

I did not find my mate, much as Mama tried. I was married to my work and came home smelling rancid and looking ghostly pale from exhaustion. In time, though, word got out about Mama’s cooking. Instead of mothers and daughters waiting for me when I got home, there would be young families at our table; old women drinking beer and laughing with Mama; occasionally elder gentlemen widowers. Mama would pull me inside the apartment and take the wrapped package of beef from me before I could say hello. The rest of the meal would be nearly ready and she needed the cuts to feed whoever was there.

Was I lonely? In time I had a small staff of sellers and butchers and a few stalls at the market. We opened a shop, one of the first with a stove, and most importantly, its own ice room. We still salted and preserved cuts, but we could store meat overnight and serve it up hot the next day at noon with Mama’s potatoes, bread, and beer. We had some tables and chairs, and more and more people liked to sit in the shop to eat rather than bring a meal home. Mama liked the families. She made pie for the children, apple, cherry, whatever was in season.

We never got rich. I shared the profit with the staff, from the dishwasher to the butcher, to the bookkeeper. Mama worried for me.

“What about your future,” she’d say. “How will you see after yourself?”

But what did I need to keep it for? In that way, the shop was my family. I was the head and saw after each employee so they could take care of their own. But I never advised them to stay.

“Walk your own path,” I told them. “Don’t be content here working for me.”

“Go,” I tell them, yet, look at my own life. After Mama passed, I stayed on in the tenement. I liked the noise of people getting through their days, children shrieking, neighbors laughing and sometimes fighting, families gathered around tables. I liked the smell of the river, rising and receding along the slippery bank. There is too much going these days. It never ceases.

I do the butchering at night, delicately severing the cuts, wasting nothing, because we can’t afford to. Sometimes I think of my father, criss-crossing the land, stooped over at the waist while powerfully directing his maul onto the 1-inch head of a railroad spike. Because of him, everything came here, up the river and across the rail. I didn’t have to go. It is surely the overlooked privilege of our time: the staying.